The Hong Kong authorities blamed Cathay Pacific, the city’s flagship airline, for the spread of Omicron to at least 50 people in the city last month. Two crew members allegedly breached their quarantine and transmitted the highly transmissible variant across the city while out shopping or visiting with friends.

Infection flow charts were published as the number of cases climbed, and the government began inquiries and threatened legal action because of the rising numbers. State media and pro-Beijing figures called for retribution.

The airline had just come off a government ban on flying key international routes, a punishment for carrying Covid-positive passengers. Around the same time, the ban was imposed in late December; quarantine rules were tightened after a pilot-tested positive, and then again just days later after three crew also did, and then again after the latest incidents.

Hong Kong’s Cathay Pacific continues to be hampered by government travel restrictions, both for its passengers and its crews, an issue that has lately resurfaced.

Cathay CEO Augustus Tang issued an update on Monday saying that the limitations affect both the carrier’s passenger and lucrative cargo businesses.

“In late December and then early January, the Hong Kong SAR Government further tightened aircrew quarantine requirements and travel restrictions,” Tang said in a statement. “These measures will have a significant impact on our passenger and cargo flight capacity.”

Tang estimates that this month’s passenger capacity is roughly 2% of its pre-pandemic capacity, while cargo capacity is around 20%.

A government exemption granted to Cathay Pacific flight crews to avoid quarantine and instead isolate at home was recently revoked by the Hong Kong government. The length of the quarantine has also been increased. As a result of the new policy, freight flights were halted for one week towards December.

On top of all that, due to an increasing number of cases of the omicron variant being reported, Hong Kong’s authorities temporarily restricted air travel out of eight countries late last month. Travellers from 150 countries and territories were banned from entering Hong Kong International Airport for transit purposes a week later.

At least HKD 1 billion (AUD 181.4 million) every month is expected to be burned by Cathay from February.

It is an open question whether Cathay Pacific is in severe trouble and if it will survive. There is little that Cathay Pacific can do about COVID-19 and the associated government restrictions; therefore, the airline is entirely reliant on Hong Kong’s government — as well as the government of mainland China.

When international travel plummeted in 2020 and 2021, the entire aviation industry suffered, but Cathay was particularly vulnerable since it had no domestic market to fall back on.

Flights between Hong Kong and London were reduced from five to one per day. The airline shifted its focus to cargo, but this, too, suffered. Despite getting a $5 billion government bailout in June of that year, Cathay recorded a HK$21.8 billion (AU$3.95 billion) loss in 2020 and laid off hundreds of employees. In the first six months of 2021, a $972 million deficit was announced.

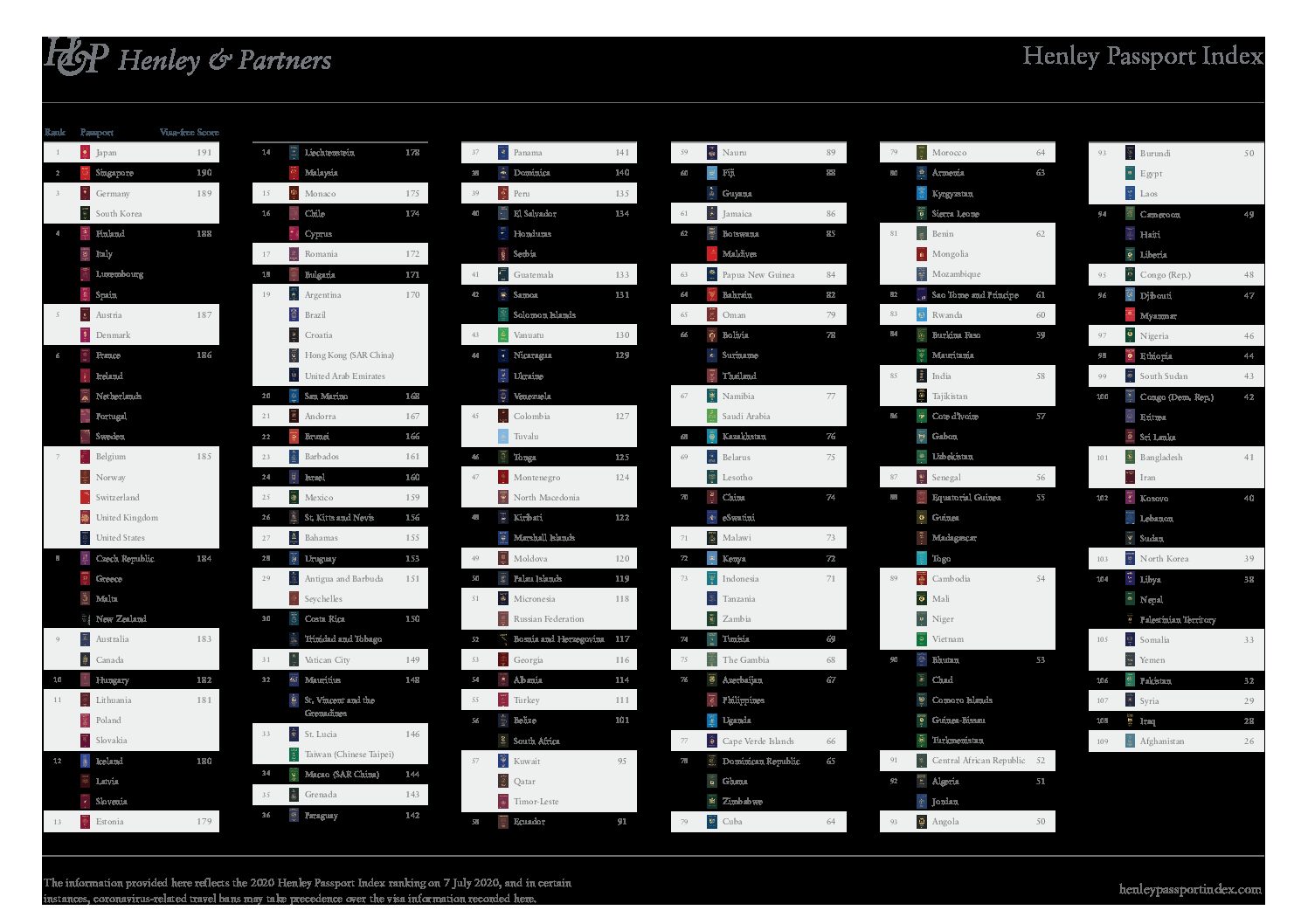

With bans on flights from seven countries and transit passengers from another 140, Hong Kong’s pandemic border restrictions are among the strictest in the world. Only 165 individuals flew into what was once one of the world’s ten busiest airports on a single day last week.

Arrivals are subjected to a costly 21-day quarantine, while thousands of close contacts are also required to enter government quarantine at Penny’s Bay. Following the Omicron outbreak, the facilities neared breaking point this week, with reports of power outages, food shortages, and people being held longer than necessary because the staff were too overwhelmed to release them.